Implications for investors

Excerpts from the report: An investor’s guide to net zero.

DISCOVER

Understanding the investment risks and opportunities created by what may be the largest redeployment of capital in history

Excerpts from the report: An investor’s guide to net zero.

1.The nature of around US$100 trillion worth of investment will be very different in the net zero scenario compared to business as usual – this creates opportunities and risks.

2.The firms which profit most from the transition will not necessarily be the ones making most of the green investment.

3.Mining activity is set to increase significantly as demand for metals and minerals used for transition-related technology (i.e., lithium) soars.

4.Incumbents from all sectors, but especially energy and utilities, should play a key role in making net zero a reality; but if they don’t do the green investment, new players will.

Investors can do more to ensure the funds they manage are aligned with the Paris climate goal, and that the companies in which they invest are making the investments necessary to turn these pledges into reality

Shamik Dhar

Chief Economist

.png)

Our report, An investor’s guide to net zero by 2050, shows massive capital investment in lower-carbon infrastructure is needed for the world to comply with the Paris climate goals. But there are obstacles.

* Cumulative investment between now and 2050 under business-as-usual (BAU) and net zero scenarios.

While most of the heavy lifting will be done by the private sector, policymakers have a vital role to play in overseeing the transition: setting clever and reliable policy can encourage private sector investment.”

Head of climate economics, Fathom Consulting

While most of the heavy lifting will be done by the private sector, policymakers have a vital role to play in overseeing the transition: setting clever and reliable policy can encourage private sector investment.

Head of climate economics, Fathom Consulting

For one, not everyone agrees with the capital spending estimates of what it will take to “green” the world.

It is complicated by things such as technological progress, the rate GDP growth and the fact there is no consensus on precisely what should be considered ‘green’ investment, the report’s authors say. For example, if industrial-scale lithium-ion batteries become the primary source of electricity storage, much of the gas infrastructure would be rendered useless and scrapped, resulting in a different level of investment to reach net zero than if hydrogen was part of the future energy mix and gas infrastructure could be retained and repurposed, say the report’s authors. Likewise, the report reads, the ability to use existing aircraft will depend on which low-carbon aviation technology becomes established.

|

Cumulative values between now and 2050

|

USD trillion 2020 prices |

|---|---|

|

Economy-wide investment |

396,6 $ – 597,0 $ |

|

Green investment |

61,4 $ – 166,1 $ |

|

Stranded assets |

4,2 $ – 22,4 $ |

Source: BNYM/Fathom Consulting. Date as of September 2022

Model output ranges following adjustments to capital stock to GDP ratio, depreciation rates, GDP growth rates and the clean capital share of total capital.

Source: BNYM/Fathom Consulting. Date as of September 2022

Some corporates must either absorb significant losses or will need to be compensated for these necessary losses. This is the greatest challenge in meeting the Paris climate goal. Our analysis also shows the amount of assets that are stranded rises the longer the transition gets delayed.

The sectors that need most of the investment to achieve net zero by 2050, are, it seems, at least in part, being shunned by some investors for the very same reasons.

According to the paper, around US$20 trillion of polluting assets will likely need to be scrapped or retrofitted: these are referred to in the report as ‘stranded assets’. Energy, utilities and airline sectors face some of the most significant costs in scrapping polluting assets, say the report’s authors. They purport that half of all corporate investment required for net zero by 2050 must be spent by firms in the energy and utilities sectors – even though their combined market capitalisation is just 6% of the total.

|

Sector Name

|

Investment 2020 prices, USD bn¹

|

Investment, % of total

|

Market Cap, % of total

|

PPE, USD bn²

|

Market cap to PPE ratio

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Energy

|

3,113

|

26.6

|

2.8

|

847

|

1.2

|

|

Utilities

|

2,408

|

20.6

|

2.5

|

1,161

|

0.8

|

|

Communication services

|

705

|

6.0

|

11.2

|

828

|

5.0

|

|

Capital goods

|

655

|

5.6

|

5.9

|

193

|

11.3

|

|

Materials

|

511

|

4.4

|

2.8

|

260

|

4.0

|

|

Automobiles & components

|

478

|

4.1

|

2.0

|

184

|

4.0

|

|

Health care

|

441

|

3.8

|

12.9

|

288

|

16.5

|

|

Information technology

|

418

|

3.6

|

25.6

|

354

|

26.7

|

|

Airlines

|

418

|

3.6

|

0.3

|

135

|

0.8

|

|

Retailing

|

390

|

3.3

|

7.4

|

367

|

7.5

|

|

Food & staples retailing

|

327

|

2.8

|

1.8

|

210

|

3.2

|

|

Air freight & logistics

|

302

|

2.6

|

0.7

|

90

|

3.0

|

|

Financials

|

247

|

2.1

|

11.6

|

378

|

11.3

|

|

Real estate

|

229

|

2.0

|

2.4

|

456

|

2.0

|

|

Road & rail

|

226

|

1.9

|

1.0

|

130

|

2.7

|

|

Hotels, resorts & cruise lines

|

212

|

1.8

|

0.7

|

88

|

2.9

|

|

Food products

|

172

|

1.5

|

1.1

|

58

|

6.9

|

|

Beverages

|

133

|

1.1

|

1.5

|

40

|

13.9

|

|

Household & personal products

|

123

|

1.1

|

1.5

|

42

|

13.4

|

|

Restaurants

|

64

|

0.5

|

1.1

|

67

|

6.2

|

|

Consumer durables & apparel

|

54

|

0.5

|

1.1

|

26

|

16.2

|

|

Commercial & professional services

|

47

|

0.4

|

0.9

|

35

|

9.6

|

|

Tobacco

|

24

|

0.2

|

0.7

|

8

|

29.7

|

|

Casinos & gaming

|

21

|

0.2

|

0.3

|

73

|

1.5

|

|

Total

|

11,719

|

|

|

|

|

¹ Total green investment required by each S&P 500 sector by 2050, net zero

scenario. Constant, 2021 prices

² Property, plant and equipment.

The report’s authors have created a new and unique methodology and used it to score 24 stock market sectors on their transition risks. How quickly decarbonization is likely to happen in each sector and how problematic, from an economic point of view, that is likely to be.

|

Sector Name

|

Overall transition risk

|

“Carbon tax 1”

|

“Carbon tax 2”

|

Carbon tax + transition speed

|

Transition speed 1

|

Transition speed 2

|

Stranded assets 1

|

Stranded assets 2

|

Stranded assets 3

|

Disclosure

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Utilities

|

2,0

|

3,6

|

2,3

|

4,2

|

3,4

|

3,2

|

0,5

|

1,9

|

0,0

|

-0,8

|

|

Energy

|

1,6

|

0,8

|

3,3

|

4,5

|

0,2

|

-0,3

|

2,2

|

1,0

|

2,0

|

0,6

|

|

Airlines

|

1,2

|

2,5

|

1,1

|

0,1

|

-0,8

|

-0,3

|

1,9

|

1,9

|

4,0

|

0,1

|

|

Road & rail

|

0,3

|

0,0

|

-0,4

|

-0,1

|

-0,2

|

-0,3

|

1,3

|

2,9

|

-0,2

|

-0,3

|

|

Real estate

|

0,2

|

-0,5

|

-0,6

|

-0,4

|

2,4

|

3,2

|

-1,1

|

-0,1

|

-0,3

|

-0,4

|

|

Hotels, resorts & cruise Lines

|

0,1

|

0,0

|

0,1

|

0,2

|

-0,6

|

-0,3

|

0,4

|

-0,1

|

0,7

|

0,6

|

|

Materials

|

0,0

|

0,2

|

0,1

|

0,4

|

-0,4

|

-0,3

|

0,2

|

0,0

|

-0,2

|

-0,4

|

|

Food products

|

0,0

|

-0,4

|

0,0

|

0,0

|

-0,3

|

-0,3

|

0,9

|

0,2

|

-0,2

|

-0,3

|

|

Automobiles & components

|

-0,1

|

-0,4

|

0,8

|

1,3

|

-0,5

|

-0,3

|

-0,3

|

-0,6

|

-0,2

|

-0,3

|

|

Capital goods

|

-0,1

|

-0,4

|

0,0

|

0,0

|

-0,8

|

-0,3

|

0,4

|

-0,2

|

-0,3

|

0,8

|

|

Casinos & gaming

|

-0,1

|

-0,4

|

-0,7

|

-0,5

|

0,8

|

-0,3

|

-1,2

|

-0,5

|

-0,3

|

2,1

|

|

Air freight & logistics

|

-0,1

|

0,1

|

0,2

|

-0,1

|

-0,8

|

-0,3

|

1,0

|

0,5

|

-0,3

|

-1,5

|

|

Consumer durables & apparel

|

-0,2

|

-0,5

|

-0,5

|

-0,3

|

-0,5

|

-0,3

|

-0,5

|

-0,7

|

-0,4

|

1,7

|

|

Food & staples retailing

|

-0,3

|

-0,3

|

-0,6

|

-0,4

|

-0,4

|

-0,3

|

0,1

|

-0,1

|

-0,3

|

-0,3

|

|

Restaurants

|

-0,3

|

-0,4

|

0,0

|

0,1

|

-0,7

|

-0,3

|

-0,5

|

-0,3

|

-0,4

|

-0,1

|

|

Beverages

|

-0,3

|

-0,4

|

-0,2

|

0,0

|

-0,5

|

-0,3

|

0,2

|

-0,2

|

-0,4

|

-1,1

|

|

Communication services

|

-0,3

|

-0,5

|

-0,7

|

-0,5

|

0,6

|

-0,3

|

-1,3

|

-1,0

|

-0,4

|

1,0

|

|

Retailing

|

-0,4

|

-0,4

|

-0,6

|

-0,4

|

-0,3

|

-0,3

|

-0,8

|

-0,6

|

-0,4

|

0,5

|

|

Health care

|

-0,4

|

-0,5

|

-0,7

|

-0,5

|

-0,2

|

-0,3

|

-0,7

|

-0,7

|

-0,4

|

0,6

|

|

Household & personal products

|

-0,4

|

-0,4

|

-0,5

|

-0,4

|

-0,2

|

-0,3

|

0,5

|

-0,1

|

-0,4

|

-1,7

|

|

Tobacco

|

-0,4

|

-0,4

|

-0,4

|

-0,2

|

-0,1

|

-0,3

|

0,3

|

-0,1

|

-0,4

|

-2,2

|

|

Commercial & professional Services

|

-0,4

|

-0,5

|

-0,7

|

-0,5

|

-0,3

|

-0,3

|

-0,8

|

-0,9

|

-0,4

|

0,6

|

|

Financials

|

-0,4

|

-0,5

|

-0,7

|

-0,5

|

0,3

|

-0,3

|

-1,2

|

-1,0

|

-0,4

|

0,4

|

|

Information technology

|

-0,6

|

-0,5

|

-0,7

|

-0,5

|

-0,4

|

-0,3

|

-1,3

|

-1,1

|

-0,4

|

0,2

|

Note: all variables and ratios have been calculated and adjusted so that higher

scores reflect more exposure to transition risk.

Green = relatively low transition risk; red = relatively high transition risk.

Source: BNYM / Fathom Consulting. Date as of September 2022

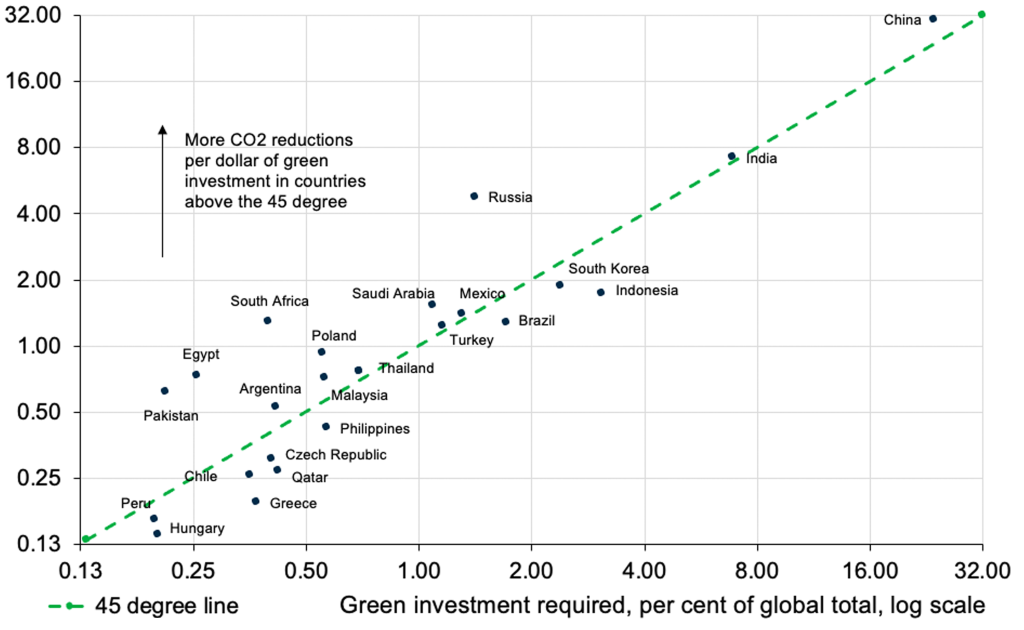

There are a few reasons for this. First, the country is large and already accounts for more than 15% of global GDP. Second, it is expected to grow faster than most economies between now and 2050 and more investment, including green investment, will be needed to support this growth. Third, a higher-than-average share of electricity production in China comes from fossil fuels and the country also has an above-average CO2 intensity of GDP.

1.

Each dollar of green investment in an EM may achieve more decarbonization than the equivalent amount spent in an advanced economy.

2. India, China, South Korea and Indonesia are expected to grow faster than the global average and currently use a lot of coal for electricity generation. Consequently, they require a larger share of green investment than their current share of global GDP.

3.

Around a third of investment will need to be spent in the US and EU combined.

Source: Source: Penn World Table / Refinitiv Datastream / BNYM / Fathom

Consultiong

*In net zero by 2050 scenario

Source: BNYM / Fathom Consulting. Date as of September 2022,

Source: Penn World Table / Refinitiv Datastream / BNYM / Fathom Consulting. Date as of September 2022

They may do a lot of the heavy lifting but much of it will probably need to be done by households and governments, by, for example, purchasing electric cars, buying new, green heating systems and insulating their homes and buildings. Funding for this should come from a range of sources including earnings, tax revenues and bank loans.

Some of the low-hanging fruit has not yet been picked. One example is the switch from coal-powered generation to renewables: financing this switch can provide a wide-ranging impact, including cost savings for households on their electricity bills, leading to wider social benefits. Such investment doesn’t just make sense for the climate, it makes business sense too.

Chief Economist, BNYM

View our team biographies to learn more.

Chief Economist BNY Mellon Investment Management

Shamik Dhar has 36 years’ experience as an economist. Starting his career in H.M. Treasury as an economist assistant in the mid-1980s, he moved to Oxford Forecasting and then spent most of the 1990s as a senior economist in the Bank of England, where he worked on the UK economic forecast in the early days of inflation targeting and on monetary policy analysis in the early days of the Monetary Policy Committee.

Shamik moved to Aviva Investors (formerly Morley Fund Management) in 2000 and spent the next 14 years in the City of London, ending up as Head of Investment Strategy. Un 2014 he became the chief economist at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in a period of rapid geopolitical and economic change, advising ministers and senior officials on the economics of Brexit. Shamik joined BNY Mellon Investment Management as global chief economist in October 2018.

Shamik has a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics from Oxford University and a master’s in economics from Queen Mary College, University of London. He also spend a year as a visiting scholar at the University of Pennsylvania in the mid-1990s.

Jake Jolly is a Senior Investment Strategist at BNY Mellon Investment Management. In this role, he is a primary contact for the firm’s largest and most complex clients, providing ongoing updates on the market outlook, investment philosophy, process, and performance across asset classes. He produces rigorously researched market commentary and investment content to shape investment strategy decisions. Jake collaborates with portfolio managers and researchers across BNY Mellon Investment Management’s investment firms to provide a vital link between investment, product, and distribution teams.

Prior to joining BNY Mellon Investment Management in 2021, Jake was a Portfolio Manager at systematic quant manager Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA) for more than four years. At DFA, he managed the firm’s flagship $16B US Small Cap equity fund, among other factor-based strategies. Before DFA, Jake worked as an emerging markets economist at IHS Markit (formerly IHS Global Insight).

Originally from Northern California, Jake received his B.A. degree in Economics and International Studies from the University of California San Diego (UCSD). He is also a graduate of Brandeis University, where he earned an M.A. degree in International Economics and Finance, and from Carnegie Mellon University’s Tepper School of Business, where he earned his MBA. At Carnegie Mellon, Jake was awarded the distinction of being the graduating MBA with the highest academic achievement in Finance. Jake Jolly is CFA® charterholder.

Sonia Meskin is the US Macro Head in the NY office. Previously, she held roles with the International Monetary Fund, Standard Chartered Bank and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. In these roles, Sonia held chief responsibility for the analysis of macroeconomic and market developments for external clients as well as internal senior management and policy stakeholders. Sonia received her undergraduate degree from the University of Pennsylvania and her Masters degree from the London School of Economics.

Aninda Mitra is a Vice-President and the Head of Asia Macroeconomics and Investment Strategy at BNY Mellon Investment Management Singapore Pte Ltd. He is based in Singapore and reports directly to the Global Chief Economist for BNY Mellon Investment Management. He is the primary contact for the firm’s clients, prospects and consultants in the APAC region for providing ongoing updates and insights about the economic, market and investment outlook on China and other major Asian economies, as well as implications for asset classes.

Mr. Mitra has twenty five years of experience in the financial services industry. Prior to joining BNY Mellon IM’s Global Economics and Investment Analysis team, he was a Senior Sovereign Analyst at Mellon Investment Corporation (formerly Standish Mellon) for more than seven years where he was responsible for fixed-income macro research for Asian and Mid-East markets. Before that he was employed on the sell-side as Head of Southeast Asia Economics at ANZ bank, and, prior to that as a Senior Sovereign Analyst at Moody’s where he managed the ratings of a diverse portfolio of APAC sovereign credits. He began his career, in the U.S., as a Country and Banking Risk Analyst at Wells Fargo. Aninda holds an M.A. Economics from, and was a Bryan Fellow at, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and a B.S. Economics (Magna Cum Laude) from Bridgewater College.

Sebastian Vismara is a Financial Economist in the Global Investment Strategy team at BNY Mellon Investment Management. His responsibilities include conducting analysis on the global economy, financial markets and investment implications.

Prior to this role, Sebastian spent 5 years at the Bank of England working on global macroeconomic analysis and financial market research. In his last role he provided macro financial research support for Governor Carney's international meeting engagements.

A native of Italy, Sebastian has a two-year Masters in Management with a concentration in Finance from the London School of Economics and an undergraduate degree in International Relations with a concentration in Economics from the University of Florence in Italy.

The conclusions and views expressed in this paper are derived from that research and are the opinion of the authors and do not constitute advice. All charts and data tables are provided for illustrative purposes only and are not indicative of the past or future performance of any BNY Mellon product.

FATHOM AND BNY MELLON INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT PARTNERSHIP

Since 2019, Fathom Consulting has provided bespoke macroeconomic modelling and scenario analysis for BNY Mellon IM’s quarterly economic and investment

outlook publication, Vantage Point.

Quarterly meetings are held to decide the key questions that will inform developments over the forecast horizon so that Fathom can conduct detailed scenario analysis that is theoretically founded, empirically driven and consistent with BNY Mellon IM’s house views. This helps to inform stakeholders of the outlook for the economy and markets, as well as the risks.

Fathom also engages in other bespoke projects for BNY Mellon IM, such as the work and analysis involved in the production of this research. BNY Mellon IM hired Fathom Consulting to provide expertise on the economics of climate change and undertake certain elements of this project. The final output, presented in this report, reflects the efforts of both parties.

The modelling framework and report conclusions were developed in collaboration, while Fathom’s proprietary climate data and tools were used to develop the sectoral risk framework presented in this report.

1This was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe

FOR INSTITUTIONAL, PROFESSIONAL, QUALIFIED INVESTORS AND QUALIFIED CLIENTS. FOR GENERAL PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION IN THE U.S. ONLY.

This report has been provided for informational purposes only and is subject to significant limitations. The views contained herein are not to be taken as advice or a recommendation to buy or sell any investment. The information contains projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets or expectations, and is only current as of the date indicated. Targets contained herein are based upon an analysis of historical and current information and assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never occur. If any of the assumptions used do not prove to be true, results may vary substantially. Certain information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. We believe the information provided here is reliable, but do not warrant its accuracy or completeness. If the reader chooses to rely on the information, it is at its own risk. The information is based on current market conditions, which will fluctuate and may be superseded by subsequent market events or for other reasons. We do not undertake to advise you of any change in the information contained in this report. The report does not reflect actual trading and other factors that could impact future returns. Given the inherent limitations of the assumptions, this report does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any securities or products. The information has been provided without taking into account the investment objective, financial situation or needs of any particular person. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be and should not be interpreted as recommendations. Please consult a legal, tax or financial professional in order to determine whether an investment product or service is appropriate for a particular situation.

There is no guarantee that any strategy which considers ESG factors will be successful, or that any strategy will reflect the beliefs or values of any particular investor. Because ESG criteria exclude some investments, investors may not be able to take advantage of the same opportunities as investors that do not use such criteria.

All investments involve risk including loss of principal.

Not for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country in which such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation. This information may not be distributed or used for the purpose of offers or solicitations in any jurisdiction or in any circumstances in which such offers or solicitations are unlawful or not authorized, or where there would be, by virtue of such distribution, new or additional registration requirements. Persons into whose possession this information comes are required to inform themselves about and to observe any restrictions that apply to the distribution of this information in their jurisdiction.

There is no guarantee that any strategy that considers environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors will be successful, or that any strategy will reflect the beliefs or values of any particular investor. Because ESG criteria exclude some investments, investors may not be able to take advantage of the same opportunities as investors that do not use such criteria.

Issuing entities

This material is only for distribution in those countries and to those recipients listed, subject to the noted conditions and limitations: For Institutional, Professional, Qualified Investors and Qualified Clients. For General Public Distribution in the U.S. Only. • United States: by BNY Mellon Securities Corporation (BNYMSC), 240 Greenwich Street, New York, NY 10286. BNYMSC, a registered broker-dealer and FINRA member, and subsidiary of BNY Mellon, has entered into agreements to offer securities in the U.S. on behalf of certain BNY Mellon Investment Management firms. • Europe (excluding Switzerland): BNY Mellon Fund Management (Luxembourg) S.A., 2-4 Rue EugèneRuppertL-2453 Luxembourg. • UK, Africa and Latin America (ex-Brazil): BNY Mellon Investment Management EMEA Limited, BNY Mellon Centre, 160 Queen Victoria Street, London EC4V 4LA. Registered in England No. 1118580. Authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. • South Africa: BNY Mellon Investment Management EMEA Limited is an authorized financial services provider. • Switzerland: BNY Mellon Investments Switzerland GmbH, Bärengasse 29, CH-8001 Zürich, Switzerland. • Middle East: DIFC branch of The Bank of New York Mellon. Regulated by the Dubai Financial Services Authority. • Singapore: BNY Mellon Investment Management Singapore Pte. Limited Co. Reg. 201230427E. Regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. • Hong Kong: BNY Mellon Investment Management Hong Kong Limited. Regulated by the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission. • Japan: BNY Mellon Investment Management Japan Limited. BNY Mellon Investment Management Japan Limited is a Financial Instruments Business Operator with license no 406 (Kinsho) at the Commissioner of Kanto Local Finance Bureau and is a Member of the Investment Trusts Association, Japan and Japan Investment Advisers Association and Type II Financial Instruments Firms Association. • Australia: BNY Mellon Investment Management Australia Ltd (ABN 56 102 482 815, AFS License No. 227865). Authorized and regulated by the Australian Securities & Investments Commission. • Brazil: ARX Investimentos Ltda., Av. Borges de Medeiros, 633, 4th floor, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil, CEP 22430-041. Authorized and regulated by the Brazilian Securities and Exchange Commission (CVM). • Canada: BNY Mellon Asset Management Canada Ltd. is registered in all provinces and territories of Canada as a Portfolio Manager and Exempt Market Dealer, and as a Commodity Trading Manager in Ontario.

BNY MELLON COMPANY INFORMATION

BNY Mellon Investment Management is one of the world’s leading investment management organizations, encompassing BNY Mellon’s affiliated investment management firms and global distribution companies. BNY Mellon is the corporate brand of The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation and may also be used as a generic term to reference the corporation as a whole or its various subsidiaries generally. • Insight Investment – Insight North America LLC (INA) is a registered investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 and regulated by the US Securities and Exchange Commission. INA is part of ‘Insight’ or ‘Insight Investment’, the corporate brand for certain asset management companies operated by Insight Investment Management Limited including, among others, Insight Investment Management (Global) Limited (IIMG) and Insight Investment International Limited (IIIL) and Insight Investment Management (Europe) Limited (IIMEL). Insight is a subsidiary of The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation. • Newton Investment Management – Newton” and/or the “Newton Investment Management” brand refers to the following group of affiliated companies: Newton Investment Management Limited (NIM) and Newton Investment Management North America LLC (NIMNA). NIM is incorporated in the United Kingdom (Registered in England no. 1371973) and is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the conduct of investment business. Both Newton firms are registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States of America as an investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Newton is a subsidiary of The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation. • Alcentra – The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation holds the majority of The Alcentra Group, which is comprised of the following affiliated companies: Alcentra Ltd. and Alcentra NY, LLC. which are registered with the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Alcentra Ltd is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and regulated by the Securities Exchange Commission. • ARX is the brand used to describe the Brazilian investment capabilities of BNY Mellon ARX Investimentos Ltda. ARX is a subsidiary of BNY Mellon. • Dreyfus is a division of BNY Mellon Investment Adviser, Inc. (BNYMIA) and Mellon Investments Corporation (MIC), each a registered investment adviser and subsidiary of BNY Mellon. Mellon Investments Corporation is composed of two divisions; Mellon, which specializes in index management and Dreyfus which specializes in cash management and short duration strategies. • Walter Scott & Partners Limited (Walter Scott) is an investment management firm authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, and a subsidiary of BNY Mellon. • Siguler Guff – BNY Mellon owns a 20% interest in Siguler Guff & Company, LP and certain related entities (including Siguler Guff Advisers LLC).

No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission.

© 2022 BNY Mellon Securities Corporation, distributor, 240 Greenwich Street, 9th Floor, New York NY, 10286

MARK-312542-2022-10-21